- Why Mining Matters

- Jobs

- Safety

- Environment & Operations

- FAQ

- Links

- Fun Stuff

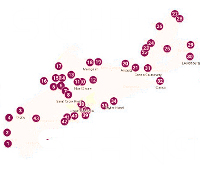

You are here

Chegoggin Point

Quiet Chegoggin Point, about as far southwest as you can go in Nova Scotia, has a surprising industrial history. Its silica was used at the Sydney steel mill and its garnet was tested at the Ford plant in Detroit. The site is a lovely lake today.

Chegoggin Point has a deposit of quartzite, which, when extracted and crushed, is 99% pure silica, a high-quality sand.

According to a 1919 report by the Geological Survey of Canada, the deposit is “350 feet thick and extends for many miles to the northeast….” It went on to say, “an unlimited supply is available. It is also favourably situated for shipment at low cost” being adjacent to tidewater and only half a mile from the Government Wharf.

The site was also only 3.5 miles from the railroad and in 1923, the Canadian Pacific Railway’s Department of Colonization and Development studied the area, which was on the farm of Edward Cushing and others at that time. After examining the silica deposit and a nearby garnet deposit, CPR concluded that “These deposits represent enormous tonnages of commercial materials that are excellent situated for mining and shipping. This will compensate to a large extent for their remote situation from a manufacturing centre.”

In 1945, a 150-pound sample of quartzite was extracted and another 50 pounds was taken from adjacent fields. It was sent to the Nova Scotia Technical college for crushing and analysis.

Some of it was also sent to the Sydney steel plant for testing as potential material for making silica bricks, which are heat-resistant and often used in things like furnaces and coke ovens.

The Dominion Steel Corporation’s (DOSCO) chief engineer, W. S. Wilson, was very impressed and wrote that “it would be a wonderful thing if we could find rock like this in Cape Breton or at least where the transportation charges would not be so high.”

Despite the cost of transporting the silica from the southern tip of Nova Scotia to the northern, DOSCO opened a quarry at Chegoggin Point and quarried silica from 1947 to 1963.

The quarry was run by Levatte Construction of Sydney on behalf of DOSCO. Mr. Levatte, interviewed in 1986, said the quarry operated seasonally during the summer months. The rock was blasted and crushed onsite to four-inch chunks. It was then transported by rail to Sydney using a branch line that went into the quarry property.

At the end of each season, the company blasted the required tonnage for the following year. When Levatte Construction returned in the spring, the quarry was dewatered, and the rock blasted the prior year was crushed and transported.

Because of this procedure, Levatte said in 1986 there were 8,000 tonnes of blasted rock laying on the floor of the idle quarry. (The quarry was dewatered a few years later during exploration work and no such stockpile was found.)

Levatte said DOSCO officials were so pleased with the quarry’s 99% purity that they were reluctant to accept purity of 97-98% from other sites even though it far exceeded requirements for producing silica bricks.

This changed when ownership of the Sydney steel mill changed. The new owners decided to source silica of lower quality but within 10 miles of Sydney. They closed the Chegoggin Point operation.

The silica quarry, now a long lake, has been explored intermittently ever since. It is estimated that over nine million tons of high-grade silica remains in the ground.

Just west of the silica quarry, along the shore, is an outcrop of schist rock that contains garnet.

About 1892, J. D. Huntington investigated the garnet as a potential source of abrasive. Several pits were dug, including one that was 18 feet deep and about 500 feet from the shore. Some of the extracted material was crushed in a 10-stamp mill that Huntington had built in 1890 to crush quartzite as part of an unsuccessful search for gold in the area. (Huntington mistakenly believed the quartzite/silica deposit was a massive quartz vein and since much of Nova Scotia’s gold is hosted in quartz veins, he thought he had a gold mine on his hands.)

The Geological Survey of Canada’s 1919 report said the remains of Huntington’s kiln were still onsite at that time, part of a crude attempt to produce a crushed garnet concentrate. A local “informant” told the GSC that “100 barrels of the powdered material were sent to the United States, and that emery wheels and stones, some of which were seen by the local people and proved to be excellent, were made of this material."

(Emery is a rock that is often used in grinding and polishing devices, and Huntington was trying to have the crushed garnet used in its place. While emery wheels and stones are often used in industrial applications, emery boards are a familiar tool for filing fingernails and toenails.)

In 1931, Duncan Cameron was exploring the garnet deposit and discussing it with the Brewerton Coal Corporation of Chicago. Cameron had extracted an 800-pound sample at the beginning of the year from the outcrop on the shore and had it crushed and sized for sand blasting. Cameron believed the garnet would be a better cleaning product than the sand.

Cameron had the Chegoggin Point garnet tested at the Ford plant in Detroit, which did regular sand blasting to clean castings. A comparison was done, and Cameron said the garnet cleaned and polished the castings in 10 minutes to a level that took 30 minutes with sand. After 20 minutes, the sand was so pulverised that it was no longer of use, but over half the garnet was still useful after 30 minutes.

The results were impressive enough that Cameron spent four weeks working the site and spent $800 in labour to extract more garnet for testing. If the larger tests were as successful as the initial one at Ford, Cameron planned to build a crusher and screening facility, extract one thousand tons per day and ship the material from a dock he also planned to build.

Unfortunately, Cameron’s plan did not come together and the garnet deposit has never been mined commercially.